Creating places that enhance the human experience.

Useful options

Beautiful snippets

Amazing pages

Building Hospital Acquired Infections -A Major Problem

Infectious diseases in humans can be caused by pathogenic organisms such as bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses through contact with contaminated surfaces in the environment, by insects and other vectors, through contact with contagious animals and human beings, direct transmission of body fluids, and a variety of other ways. Nosocomial infections on the other hand are infections acquired in hospitals and nursing homes, which affect an estimated 10% of all hospitalized patients, causing urinary tract infections, wound infections, pneumonia, or blood stream infections. They are important causes of morbidity and mortality, and represent a significant economic burden to third party payers and society. According to an estimate from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nosocomial infections generate costs of over 5 billion per year.

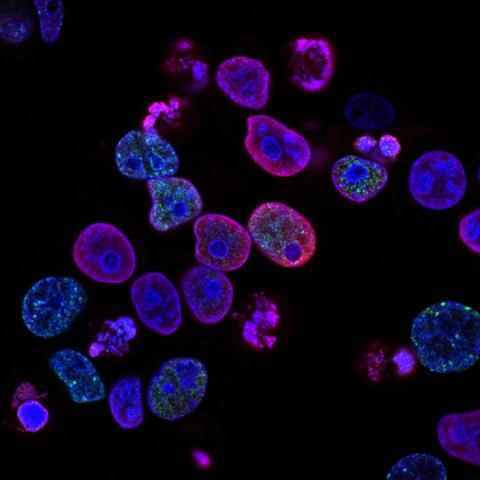

Patients with compromised immune functions (including the elderly and the very young) are especially susceptible. Nosocomial infections are acquired through direct contact from hospital staff, patient-to-patient transmission, inadequately sterilized instruments, invasive interventions, or even via the food or water provided at hospitals. Most hospital-acquired infections are caused by bacteria, in particular by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp. These infections are usually treated with a combination of several antibiotics.

It has been observed that patients in the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) get hospital-acquired infections more frequently than those patients who are on the standard wards of the hospital. Within the ICU environment infections are often caused by Multidrug Resistant (MDR) bacteria. The consequences of nosocomial infections in the ICU can range for an extended stay in the ICU to life-threatening infection and death. In particular, blood stream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia have a poor prognosis, and in many cases an associated mortality of up to 40% of affected patients. The exact incidence of nosocomial infections is unknown, but it is estimated that over 2 million nosocomial infections occur annually in the United States and about 1.2 million such infections occur in Europe.

Current and Future Treatment of Nosocomial Infections

The mainstay of current medical treatment of nosocomial infections is antibiotic therapy, usually given in a combination of up to three agents. Although antibiotics have been successfully used over the past decades, the emergence of virulent, antimicrobial resistant strains of bacteria has become a major problem, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. In up to 60% of infectious diseases, the infecting strain is resistant to the best drug available. This is especially true for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus (e.g. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA).

The risk of dying from a serious infection in an intensive care setting is estimated to be as high as 50%. In addition, the extension of the ICU/hospital stay, the necessary medication and additional intensive care interventions are very costly. There is a very high unmet medical need for drugs that effectively fight serious infections and benefit patients who are particularly susceptible to nosocomial infections, such as immunocompromised individuals and neonates.

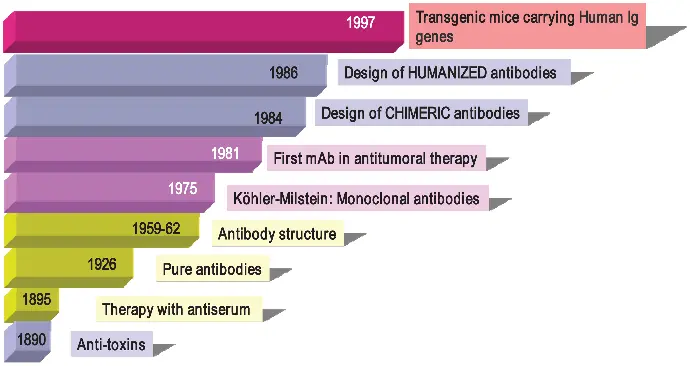

For the human immune system antibodies are the workhorse of the humoral immune response, allowing the targeting of invading pathogens by highly specific antibodies, and thereby initiating and promoting an appropriate immune reaction up to the elimination of the pathogen. Recently the interest using antibodies as therapeutic agents for the treatment of infectious diseases has been fueled by two factors: Encouraging clinical experiences with antibodies targeting bacterial pathogens (e.g. S. aureus) as well as the excellent safety profile of monoclonal antibodies. Therefore the concept of combining monoclonal antibodies with standard-of-care antibiotics for the therapy has been emerging as a novel way to treat severe hospital-acquired infections.

There are many advantages to using therapeutic antibodies in addition to current therapy:

Monoclonal antibodies are in general safe and well tolerated.

Monoclonal antibodies complement and improve antibiotic therapy without interfering with antibiotics (due to the different mode of action). Combination treatment with antibiotics may lead to more rapid resolution of infection, resulting in shorter stays in ICUs and a significant reduction of morbidity, mortality, and health care costs.

Monoclonal antibodies have a longer half-life and require less frequent dosing than antibiotics.